Mollie Politzer was 32 years old when she got sick.

She was in the hospital for months, and when her condition eventually worsened to the point of death, her rabbi was called in. The rabbi arrived and proceeded to change her name.

He did this to fool the Angel of Death — so that when the Angel of Death came, he wouldn’t know who she was.

It worked …

Mollie Politzer survived. She changed her name back. She lived to be 87.

Ira Glass tells this story to open the March 7, 1997 episode of This American Life, called “Name Change.” Mollie Politzer was his grandmother. Changing her name had saved her from death.

If only David Hackney could have heard this story.

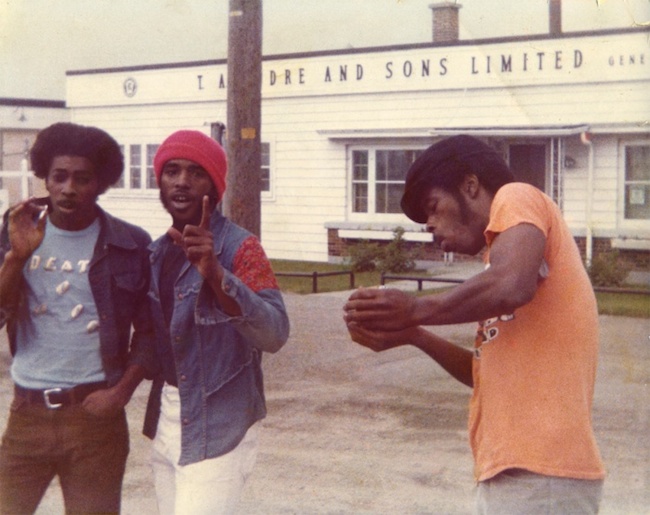

A band called Death

Detroit, Michigan in the late 60s and early 70s was the heartbeat of popular music in the United States. Legendary artists like Diana Ross and the Jackson 5 became stars in the “Hitsville, U.S.A.” house that Berry Gordy built.

Motown didn’t just produce stars, it produced legends. And the pioneering Motown sound remains instantly recognizable.

Against this backdrop, the incredible story of Detroit’s own Bobby, Dannis, and David Hackney began.

Like the most famous artists of Motown, the Hackney brothers grew up with the Motown sound all around them. But that’s not the music that spoke to them, that spoke through them.

Inspired by the likes of Alice Cooper, the African-American Hackney brothers played “white-boy music” (their other brother Earl’s words, not mine) — a hard-charging brand of rock and roll that no one had quite yet figured out how to characterize.

They were punk … before punk was punk.

In the words of Questlove, “This is the Ramones … but two years earlier.”

So what happened?

What’s in a name?

By the mid-70s, the Hackney brothers had their demo tape. They had some fans too — people who had seen their flyers, who liked their distinct sound, and who wore their T-shirts with the unique, potentially iconic logo.

And they had their name.

To them, to David, Death meant rebirth. It was spiritual. He wanted his music, their music, to inspire people to view death in a positive light.

But to others, who didn’t understand, it just meant … well, death.

Arista Records, then helmed by Clive Davis, offered the Hackney brothers a record deal. But with a condition: they had to change their name. Bobby and Dannis would have. David wouldn’t even consider it.

To David, Death was the band and the band was Death. There was no separating the moniker from the music, the meaning, and the men who made it.

And so for the next 25 years, that demo tape sat in an attic. It collected dust and regret.

Were it a drink, David might have sipped it wistfully while sitting on his Detroit porch as he strummed his guitar, while somewhere out there Dannis and Bobby made their way as reggae musicians.

In the year 2000, by all accounts, David was frail from years as an alcoholic. (He appeared, I imagine, not unlike what Mollie Politzer must have looked like when the rabbi came in.)

At a family wedding, David gave the demo tape to Dannis and Bobby. He told them, “Keep these safe. One day the world is gonna come looking for this music.”

He was right, of course. He just wasn’t alive to see it.

The Angel of Death found David less than a year later.

The essential question

You cannot watch A Band Called Death — the acclaimed documentary by Mark Christopher Covino and Jeff Howlett that tells the remarkable tale of the Hackney brothers — and not immediately consider this question:

Should the brothers have changed the name of the band and taken the record deal?

“It’s definitely something that David was so passionate about, there was no changing his mind,” Jeff explained to me. “He was the leader of the band, and the guys just stuck behind him. They had a lot of arguments about that. It was a very hard decision. But they just 100 percent wanted to back up their brother and let him make that decision.”

How might their lives have been different?

How might David’s life, in particular, have been different?

There are no easy answers. And you can’t begin to consider these questions in their full context until you watch the entire story.

(By the way, I’ve purposefully left out how it ends, and the unbelievable twists and turns that occur in the story’s second act, because I do not want to ruin it for those of you who have not yet seem the film. It’s available on Netflix, and you can also buy the DVD here.)

I don’t often get “goosebumps” watching anything but sports. But watching this film gave me goosebumps.

And I rarely feel tears well up in my eyes watching anything. But I did watching this.

Because it’s not so much a story about a band you never heard of (but should have). It’s really a story about family, and the bonds we can barely describe but that no one can ever break. It’s the story of brothers who always had each other’s backs, through the ups and the downs and the regrets and redemptions — just like their mama told them to.

And, most important for our purposes here, it’s a story that makes you ask a hard question of yourself. One that you need to know the answer to:

Where is your line between artistic integrity and finding a bigger audience?

Dannis and Bobby Hackney would have changed the name and taken the record deal. Imagine where they could have gone. Imagine the music they might have made. When you listen to musical icons like Questlove and Henry Rollins and Alice Cooper rave about their sound, the potential seems limitless.

David wouldn’t do it though. Couldn’t do it. Changing the name would have crossed his line.

Would it cross yours?

And would you be willing to accept the consequences?

Wait, what is artistic “integrity” anyway?

The definition of art:

The expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.

You’ll notice I bolded a part.

If art, by definition, is meant to be appreciated, then how is its integrity maintained by decisions that shield it from exactly that?

You could argue, as David might have in 1975, that the name itself is part of the art. So to be admired under a different name is to alter its expression or application, the first part of the definition.

But would David have argued that in 2000?

And are commitments to artistic “integrity” often just ego masquerading as a kind of artistic altruism?

Consider this, from the New York Times article about the band:

Part of the reason David refused was because he was writing a rock opera about death that portrayed it in a positive light, Bobby Sr. said. ‘He strongly believed that we could get a contract with another record label,’ he added. ‘We were young and cocky, but David was the cockiest of us all.’

When pride morphs into conceit, negative consequences await.

Here is what Mark Christopher Covino, one of the film’s directors, told me when I asked where his own line is … and how making A Band Called Death might have moved it:

The story of Death and David haunted me through making this movie, and it haunts me to this day.

I always think about David with things like that now. I don’t just say ‘No, it can’t be this.’ I think, okay, maybe it could be, and how would that work for the art as a whole?

I always think, what if I say ‘No’ the next time to changing the title of my own movie, or say ‘No’ to something that will get the movie finished, and the movie never gets made? And there I’ll be, 40 years from now, an alcoholic. I’m always thinking about David.

I asked Mark if he thinks that decision David made in 1975 was a fateful one:

I think it definitely played a part. I think he probably thought about that decision to say ‘No’ to Clive Davis of Arista Records for many, many years. This music, it was his life, and he wasn’t able to express it anymore to people because he felt like nobody wanted to listen to it.

He felt like nobody wanted to listen to it.

What’s so sad about that line is that so many people did want to listen to David’s music. To Death’s music. We know that now. But they just weren’t given the chance to listen.

I can’t help but wonder where David’s line would be now …

The irony of ironies

Did you catch when Mark said, “What if I say ‘No’ the next time to changing the title of my own movie”?

The movie he was referring to was A Band Called Death.

The original title that Mark and Jeff had for the film during the first four years of production was Where Do We Go From Here. It’s an appropriate title, being the name of one of the band’s songs. It would have worked okay. Mark did not want to change it.

But he did, at the behest of those managing the business aspects of the film. The movie might never have seen the light of day otherwise.

And as I told Mark, I may never have watched it had the original title remained.

Reading “A Band Called Death” caught my eye. It’s a great headline, utilizing two of the 4 U’s: unique and ultra-specific. Where Do We Go From Here is neither.

The title did what a title should do, inspiring me to read the first line, which in this context was the Netflix description. I found it irresistible: “This captivating documentary tells the story of three teenage brothers from Detroit who founded the first black punk band in the early 1970s.”

And now here I am several months since that first viewing, writing a post I need to write … because I cannot get this story out of my head, and because I know you’ll benefit from thinking about the essential question I posed above (and pose again here in a bit).

If you watch my interview with Mark, which I’ve embedded below, you are likely to get the same sense I did: that the business of filmmaking is hard, and has been hard on him.

But you will also likely get this sense: that he is proud of his work, especially A Band Called Death, and this is in large part because he and Jeff got to tell the story they wanted to tell, and share it, and spread it … save for that one little change.

In his heart of hearts, I bet Mark would love for Where Do We Go From Here to still be the title. But I don’t get the sense that he regrets making that one concession to protect the overall integrity of his vision: which was to get the film made and distributed and seen.

It saddens me to think that David may have come to this same realization, had he had the chance to do so.

But Death, the name, killed his vision for Death, the band. And unfortunately, David wasn’t around to witness its rebirth.

Fight for your art — even if you have to fight yourself first

We are creatives, you and me. That’s my assumption anyway, because most everyone who comes here to Copyblogger creates content of some kind.

That content is our art. It is how we express ourselves, and it is meant to be appreciated. In fact, for us, it needs to be appreciated. Content marketing doesn’t work without content that is appreciated by an audience.

David Hackney was creative. And he needed his art to be appreciated too. It haunted him that it wasn’t. To his credit, David somehow, despite his despair, maintained belief that someday fate would deliver Death to its audience. (Though he couldn’t have imagined how.)

But it didn’t have to be that way.

My question to you is this: Would you be willing to wait 35 years or more (or to possibly no longer even be around) for your content to have its impact on an audience?

To answer that question, you have to answer the essential question. You have to know where your line is.

And that involves understanding the difference between artistic integrity and artistic authenticity. Think about it this way:

If art is meant to be appreciated for its beauty and emotional power, and if integrity means “the quality of being honest and having strong moral principles” … then shouldn’t “artistic integrity” be defined as being honest and principled in pursuing the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination for the purposes of creating something meant to be appreciated for its beauty and emotional power?

If you agree, then shouldn’t some decisions you make be made to ensure that your art has a fair opportunity to be appreciated?

- Maybe it’s changing your name

- Maybe it’s tweaking your style

- Maybe it’s charging a reasonable price for your work so you can afford to market it or create more of it

So long as it remains authentic. So long as it changes only the body of your work, not the soul.

I can’t answer the essential question for you. No one can. Because you are the soul of your art. Your line is yours to define and toe and fight for.

But we’d all be wise to remember that sometimes to fight for our art, the most important battle is with ourselves.

I wish I could ask David Hackney if he agrees.

Well I got news for you,

That ain’t the way it’s gonna’ be.~ “Keep on Knocking” by Death

Your thoughts

I’d love to hear your thoughts — on the documentary, if you’ve seen it (or once you do), and on how you answer the essential question.

Join us over in the discussion on Google+.

Hear from the directors of A Band Called Death

Below is my interview with Mark and Jeff.

Unfortunately, we had some audio and connection issues with Jeff (who has known Dannis and Bobby since 1990), so he’s only around for the first five minutes or so. But he still provides great insight while there.

Mark and I dig deep on what happened to David and why it still haunts Mark, plus Mark’s own battles balancing artistic authenticity with the harsh realities of business, and some of the challenges that independent filmmakers still face, which even the Internet cannot fully solve. It’s a fascinating conversation.

Oh, and one more thing …

To play you out, here is my favorite song by that band called Death: “Keep on Knocking.”

This article's comments are closed.